The Cearnach McMahon

Plunder and piracy in Rineanna during the Famine Stonehall National School’s submission to the Irish Folklore Commission contains a fascinating story of the activities of a man known as the Cearnach McMahon who lived in the Rineanna area during the famine. The story is mentioned in The Story of Newmarket-on-Fergus by Rueben Butler and Máire Ní Ghruagáin and also in a 1978 edition of The Other Clare.i It goes as follows:

“The famine – period was comparatively mild in our particular corner of Tradree. The immunity from its evil effects was in great part due to the activities of a local leader, the Cearnach McMahon who lived in Ballycalla. Ships from Clarecastle carried huge quantities of grain down the Fergus on their journey to England the while the people of Clare were in want. On one occasion a grain ship was riding at anchor on the river near Rhinanna. McMahon from the mainland cut the ships cable with a bullet. The ship drifted in to Rhinanna and was captured by McMahon and his men who fed the hungry people with their spoil.”ii

While the details may not be entirely accurate, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the story was based on actual events that took place around Rineanna in the 1840s.

Pre-Famine poverty

Even before the failure of the potato crop the poverty of the people of Clare was evident in an incident that occurred at the quay of Clare (Clarecastle) in 1842. On 4 June a large crowd attacked a ship laden with meal and flour and took away about half the cargo, returning for the remainder the following night. The disturbance continued for a third night when two people were shot dead while trying to force entry into the property of the ship owner, a Mr. Bannatyne of Ennis. iii

Once the famine began in earnest in 1845 boats carrying provisions along the Shannon and Fergus came under attack with increasing regularity.

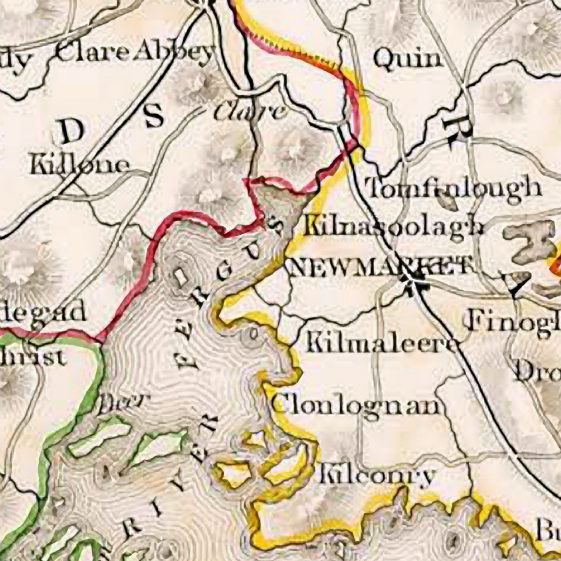

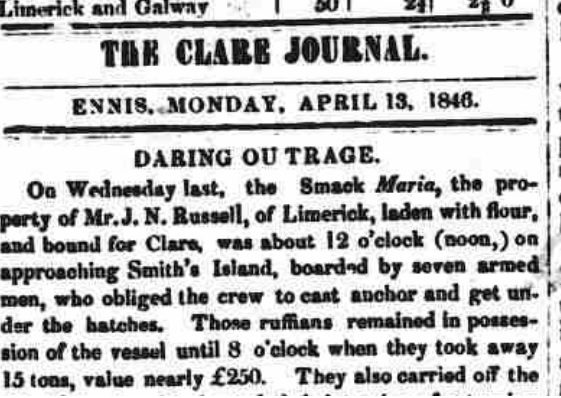

The most widely reported of these attacks occurred in April of 1846 when a boat belonging to prominent Limerick merchant named John Norris Russell was boarded by seven armed men near Smith’s Island in the River Fergus. The men ordered the master of the boat William Meskell and his crew into the cabin and proceeded to unload the cargo of flour and meal bound for Russell’s bakery in Ennis. Over the course of several hours they took possession of 15 tons worth around £250. They then instructed the crew to remain at anchor so they could return for the remainder. As soon as the men left, Meskell disobeyed the order to stay put and immediately made for Clarecastle. On reaching Clarecastle he alerted the police who set out in search of the stolen goods. Newspapers claimed that 30 sacks of flour were immediately recovered, that another 51 bags were later found hidden under ground near Hurler’s Cross and that two suspected robbers were taken into custody.iv

Some reports hint at a conspiracy when they suggest that a boat called the Royal George was allowed to pass the scene of the crime while others were ordered to stop. On reaching Clarecastle the crew of the George then gave false information about what they had witnessed thereby delaying the search for the perpetrators. v The incident caused quite a stir at the time and provoked varying levels of outrage but also some sympathy for the plunderers. One letter to the editor of the Limerick Examiner stated that while the plunder was injurious to public peace and prosperity it was “I firmly believe, perfectly necessary in the present crisis for the preservation of the lives of thousands of our famished fellow creatures.”vi

The incident even got a mention in the House of Commons when William Smith O’Brien, MP for Co. Limerick, referred to the plunder of the boat in the Fergus and expressed surprise that there hadn’t been more attacks on property given the fact that the “people were starving in the midst of plenty”vii

Whether the government paid any heed to Smith O’Brien or not they certainly listened to the merchants of the area who demanded protection for their vessels. By the end of April the Mrymidon, an iron gunship, was patrolling the waters around the Fergus to “discover the pirates” responsible for the robbery. The Mrymidon was one of many ships deployed over the coming years to protect “the meal-vessels and merchantmen from being plundered by the lawless pirate fishermen who infest these localities.”viii

In an effort to recoup his losses, John Norris Russell issued legal proceedings against the landlord Capt. James Creagh and his tenants in Kilmaleery, the parish nearest to where the robbery had occurred. The residents of Kilmaleery complained bitterly at having to shoulder the blame as the stolen plunder was taken by and used for the people of the neighbouring parish of Kilconry. But rather than point the finger at the culprits in Kilconry (who were apparently well known around the area) the Kilmaleery parishioners agreed to pay a cess (tax or levy) to meet Russell’s demand.ix

Arrests and Trials

On 13 July two men, father and son Bryan and Patrick McMahon, stood trial for having 14 tons of flour, property of John N. Russell, in their possession at Rineanna. The boat master William Meskill testified that seven men boarded the boat on the 8th or 9th of April and took away all the meal and flour. Alexander Herd, Sub-Inspector of the Police, searched McMahon’s house and found 4 sacks of flour buried and covered with earth. Thomas Reardon, who worked for Russell, identified the flour bags marked with the initials J.N.R as being the property of John Norris Russell. When cross-examined by Charles O’Connell for the defence, Reardon could not swear that the bags might not instead be the property of John Nugent Reynolds. This uncertainty on Reardon’s part seemed to sway the jurymen who acquitted the pair immediately.x The McMahon’s acquittal seemed to embolden the locals to commit further acts of piracy. In April 1847 the London Daily News reported “…that a small hooker, flour-laden, was plundered in the river Fergus on Tuesday last.”xi In May 1848 “a boat laden with meal, the property of the Messrs. Russell, was plundered in the river Fergus on her passage from Limerick. Two tons and a half of the meal are said to have been carried off by the plunderers.” xii

And in February 1849 “A sloop, the property of John Norris Russell, Esq. was boarded on Friday night in the river Fergus, on her passage to Clare Castle, by four men, two of whom were armed with blunderbusses. They beat the crew and took away two ton of Indian meal.”xiii Police made their way to Rineanna where they found large quantities of meal hidden on properties in Carrigerry and Ballycalla. Five men, Pat Morony, Pat Hickey, James Hickey, Michael McNamara and Michael Reynolds, “all notorious characters”, were arrested. This operation was performed with assistance from the Sub-Inspector at Kildysart, William Blennerhassett and he receives high praise in the pages of the Limerick Chronicle for putting an end to the ‘piratical outrages’ on the river.xiv The Hickeys, McNamara and Reynolds were each sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia and it seems their convictions put an end to the acts of plunder in the area. The local merchants indeed believed this to be the case. Shortly afterwards a notice appeared in the Limerick and Clare examiner praising Blennerhassett for “his exertions in endeavouring to put down Piracy on the Shannon and Fergus, and are of opinion that his recent capture of persons on the islands of those rivers, and in whose houses arms, quantities of flour and meal were found, will be the means of preventing repetition of their piratical depredations.” The notice is signed by J.N. Russell, Francis Spaight, James Bannatyne and other notable merchants of Limerick and Ennis.xv

So what of the Cearnach McMahon story?

The Irish word ‘cearnach’ can be translated as ‘square’ or ‘squarely’ which may refer to the man’s physical build. It may also be a misspelling of the word ‘ceatharnach’ which has various, more interesting, translations including ‘bandit’, ‘outlaw’ but also ‘champion’ and ‘hero’. While it’s difficult to say for sure, it is certainly likely that Bryan McMahon is the Cearnach of the story. A boatman by that name can be found living in Rineanna around that time.xvi Much of the rest of the story however seems to be pure fabrication. Contrary to the story’s claims that the plundered grain was leaving Clarecastle for England, newspaper reports clearly show that it was heading from Limerick to Ennis. McMahon’s capture of the boat by sending a bullet through the cable rope also seems a very unlikely feat of marksmanship. Though the details of the story may not tally exactly with the facts it is an interesting example of how real events become the basis of local myths through the exaggeration and embellishment of certain details. Rueben Butler and Máire Ní Ghruagáin say that the story’s “real value is that it expresses the deep longings of a repressed community.”xvii

The Cearnach McMahon story reflects a people desperate for heroes and justice in a time of terrible trauma and injustice.

i. The Story of Newmarket-on-Fergus by Rueben Butler and Máire Ní Ghruagáin, pg. 259 and The Other Clare Vol 2, 1978, pg. 33 ii. Schools Collection, Stonehall, Cora Caitlin, https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/5177654/5177312 iii. Sheffield Independent – Saturday 11 June 1842 iv. Limerick Chronicle – Saturday 11 April 1846 et al; v. Roscommon & Leitrim Gazette – Saturday 18 April 1846 vi. The Pilot – Monday 13 April 1846 vii. Limerick Chronicle – Wednesday 22 April 1846 viii. Limerick Reporter – Tuesday 17 August 1847 ix. Limerick Chronicle – Wednesday 27 May 1846 x. Limerick Reporter – Friday 17 July 1846 xi. London Daily News – Tuesday 20 April 1847 xii. Kerry Examiner and Munster General Observer – Friday 12 May 1848 xiii. Clonmel Chronicle – Friday 09 February 1849 xiv. Limerick Chronicle – Saturday 10 February 1849 xv. Limerick and Clare Examiner – Wednesday 28 March 1849 xvi.https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/images/marriage_returns/marriages_1864/11613/8274789.pdf xvii. The Story of Newmarket-on-Fergus by Rueben Butler and Máire Ní Ghruagáin, pg. 259

No Comments

Add a comment about this page